Living with Anxiety: Stories from Al Jalees Community

Anxiety is often spoken about in numbers, diagnoses, and headlines. This week, we chose to speak about it as a lived experience. At Al Jalees, our conversations are centered around books and culture, so this often takes us somewhere deeper. This month, we are reading The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt. As we explored a book that examines rising anxiety levels and emotional fragility, we found ourselves asking a question:

What does anxiety actually look like when it lives inside someone’s daily life?

Talking about anxiety matters because silence does not make it disappear. As a community, we want to strengthen the understanding around mental health challenges. Anxiety thrives in isolation, so it is important to say this clearly: it is okay to ask for help. You are not broken. You are not weak. You may simply be in the process of coping, healing, or carrying a heavy burden.

Our minds often trick us into believing that everyone else is coping better, managing life more smoothly, or carrying less weight. Anxiety disguises itself in exhaustion, irritability, perfectionism, constant productivity. We tend to normalize the behaviors without understanding what is driving them.

We often talk about anxiety as something to overcome or to silence. But for many people – myself included – anxiety is something we live alongside for years. It can show up through physical illness, gut pain, headaches, restlessness, or dizziness. Speaking about it openly allows us to stop treating anxiety as a personal flaw and start recognizing it as a human response to prolonged stress, uncertainty, loss, and pressure.

Asking for help remains difficult in many cultures, especially in environments that value toughness or dismiss emotional pain. Many are taught to endure hardship alone. While community spaces cannot replace professional care, they can ease isolation. Vulnerability should not be punished. Honesty should be be encouraged and met with care.

With this intention, we invited members of our community to share their personal experiences with anxiety, stress, and the long-term weight they carry. This piece is not meant to instruct or fix. It exists to acknowledge. To say: you are not imagining it, you are not alone, and your experience deserves space.

What’s Going On Beneath the Surface?

Globally, anxiety levels are rising across all age groups. According to the World Health Organization, anxiety disorders affect more than 300 million people worldwide, making them among the most common mental health conditions globally. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, studies reported a 25–30% increase in anxiety and depressive disorders.

While The Anxious Generation focuses on the systems shaping younger minds, its themes extend far beyond adolescence. Chronic stress, prolonged uncertainty, caregiving, illness, grief, and repeated emotional shocks do not disappear with age. They accumulate. When anxiety goes unaddressed, it can affect physical health, sleep, concentration, emotional regulation, and relationships. It may contribute to burnout, depression, panic, chronic illness, or withdrawal from life.

Community Stories

Amal Ghallab

This is a story about carrying fear for a long time, and continuing anyway

I am sharing my experience with anxiety and stress in the hope that it may help others. My journey began more than ten years ago, when my husband was diagnosed with bladder cancer. At first, the illness was treatable, but over time it spread. We saw this as a test of faith, believing that patience and prayer would guide us through. Things became much harder when my husband lost hope and refused treatment altogether. That period was devastating.

The emotional weight did not stay in my thoughts alone. It began to show physically in my body, and I was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes caused by extreme stress. Life moved in cycles of shock and brief recovery. When my husband’s brother passed away suddenly, grief pulled us back into a dark place. Later, my husband underwent a major surgery that permanently changed our daily life. Each emotional blow found its way back into my health, reminding me how deeply connected the body and mind truly are.

Just as things began to stabilize again, my eldest son was diagnosed with two brain tumors. One caused blindness, and the other affected his nervous system. One tumor was successfully removed, and my son can see again. The second is now being treated with intensive medication. Over time, anxiety became something I carried not only in my thoughts, but in my body. It was present in my blood sugar levels, my exhaustion, and my constant state of alertness. Through it all, faith remained my anchor. Community support, even when quiet or unspoken, made a real difference. Knowing that I was not alone helped me endure.

Today, my health is improving. I continue to pray for healing, strength, and peace for my family and myself. Anxiety has been part of my journey, but so has resilience.

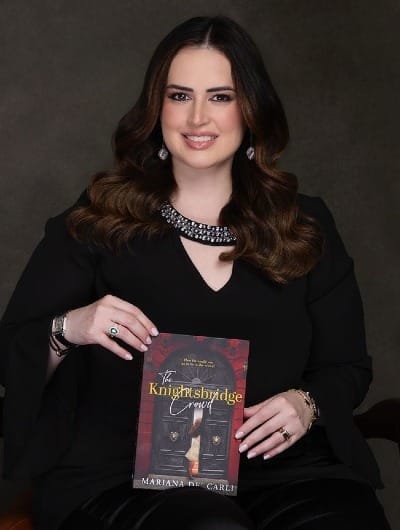

Mariana De Carli

This is a reflection on living with anxiety, and learning how to give it form rather than power.

Anxiety has never been an abstract concept for me. It has been physiological, cognitive, narrative-driven, and persistent. Long before I studied it formally, I lived it. Panic disorder and chronic anxiety shaped how I interpreted the world, how my body responded to uncertainty, and how my inner dialogue narrated competence, risk, and belonging. Even now, with years of experience and formal training behind me, anxiety does not disappear. It evolves. It becomes quieter, more analytical, and, at times, more persuasive. Much like the worlds I write about, it operates beneath polished surfaces, shaping behaviour while staying mostly unseen.

Completing an applied neuroscience degree at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience gave me language for experiences I had previously only felt. Panic became a dysregulated threat response rather than a personal failure. Hypervigilance became a predictable outcome of repeated stress exposure. This same lens underpins the psychological architecture of my fiction. In The Knightsbridge Crowd and The Marbella Crowd, anxiety is rarely named, but it is everywhere. It appears as social vigilance, image management, fear of exclusion, and the subtle panic of not quite belonging. Knowledge did not eliminate anxiety, but it allowed me to observe it, dissect it, and write it with intention rather than instinct alone.

Imposter syndrome has been one of anxiety’s most convincing disguises. It borrows the language of rigour, standards, and discernment and insists that exposure is inevitable and that legitimacy is always conditional. In the environments I write about, status is fragile and constantly negotiated, and this neuropsychological pressure resembles the internal logic of impostor syndrome itself. Neuroscience helped me recognise this voice not as insight, but as a threat narrative reinforced by prior experience and social conditioning. When the brain predicts social threat, it searches relentlessly for confirming evidence. Understanding this mechanism has been essential in separating self-assessment from self-attack, both on the page and in my own work.

Writing has always been the space where this separation becomes possible. On the page, anxiety slows down. It loses pressure and becomes structured. Narrative allows what is overwhelming in lived experience to be reframed, contextualised, and metabolised. Many of the scenes I write emerge from episodes of stress, unease, or anticipation, emotions that mirror my own anxiety responses. Publishing, paradoxically, is both exposure and regulation. It activates the systems that anxiety targets, while offering resolution through meaning. Each book then becomes a controlled confrontation with visibility, judgement, and uncertainty, themes that run consistently through my work.

There is something stabilizing about pairing literary exploration with technical understanding. When affect is held alongside the framework, panic becomes intelligible rather than consuming. When subjective experience is informed by empirical insight, it gains clarity rather than distortion. This balance has allowed my ongoing effort to write even when anxiety argues against it. Knowledge has not silenced fear, but it has diminished its authority.

I continue to publish not in spite of anxiety, but because of it. My books explore power, belonging, and psychological vulnerability precisely because these states are intimately familiar. Writing is where anxiety is converted into narrative, where impostor syndrome is countered not by reassurance but by observation, evidence, and craft. Applied neuroscience did not distance me from my inner life. It gave me the tools to interact with it more critically and more honestly. In the space between lived experience and understanding, anxiety no longer controls the story. It becomes part of what is being examined.

Anxiety Through a Literary Lens

Reading can offer a pause for the anxious mind. Research shows that reading can reduce stress levels, slow heart rate, and improve emotional regulation. Here are a few books I would like to recommend that helped me explore fear and anxiety:

Dare – Barry McDonagh

“You are not your anxiety. As abnormal as it makes you feel, this anxiety is not the real you. It is not who you are or who you have become”

“Fear and excitement are just different sides of the same coin. When wildly excited, you experience the exact same sensations as you do when you’re very anxious”

Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway – Susan Jeffers

“All you have to do to diminish your fear is to develop more trust in your ability to handle whatever comes your way!”

“The fear will never go away as long as I continue to grow.”

Good Anxiety – Wendy Suzuki

“Anxiety’s arousal, triggered by the stress response, will alert you to something that’s bothering you — a sudden change at home or work, for instance.”

“Anxiety really does work like a form of energy. Think of it as a chemical reaction to an event or situation: Without trustworthy resources, training, and timing, that chemical reaction can get out of hand — but it can also be controlled and used for valuable good.”

As a community, and as a literary family, we need to acknowledge one thing clearly: suffering alone is not an option. We need to break the cycle of shame many of us were raised with around mental health, fear, and anxiety. I am writing this as a diagnosed GAD patient, a leader, a mother, and an entrepreneur to tell you this: you are not weak because your fears or anxieties feel out of control or overwhelming. You are human.

We want to hear from you. Write back to us. Tell us what helped. Tell us what didn’t. Tell us how you are feeling as this new year begins.